Various Things Happen

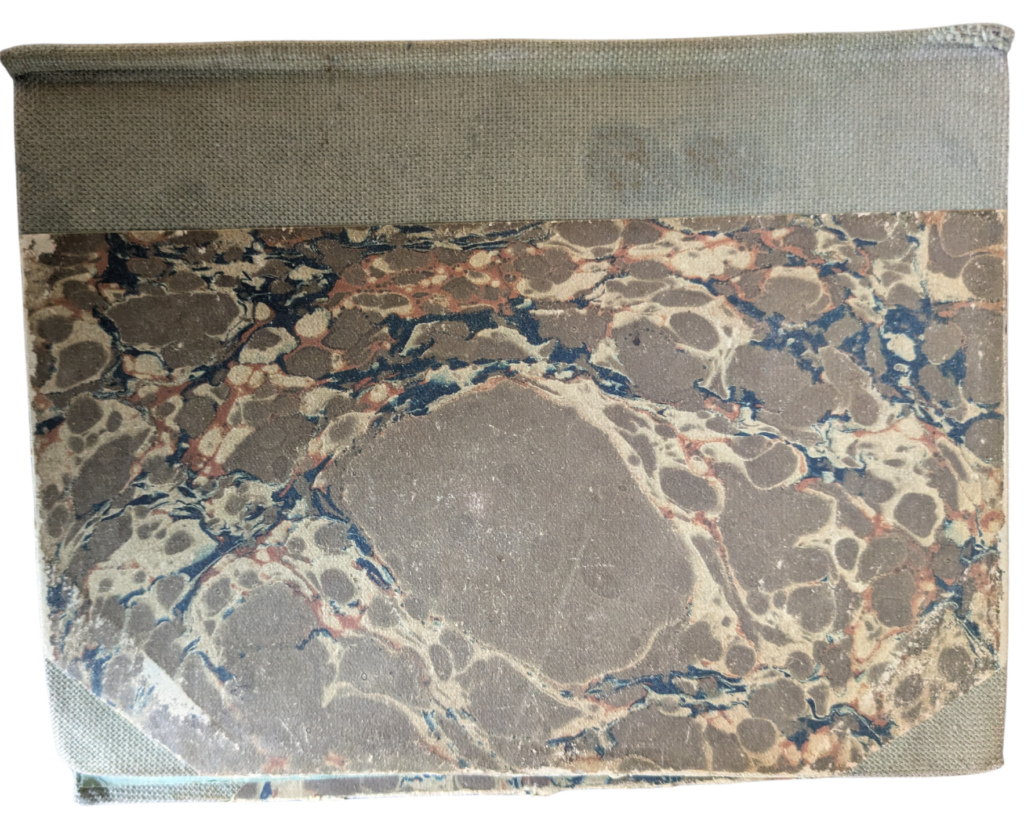

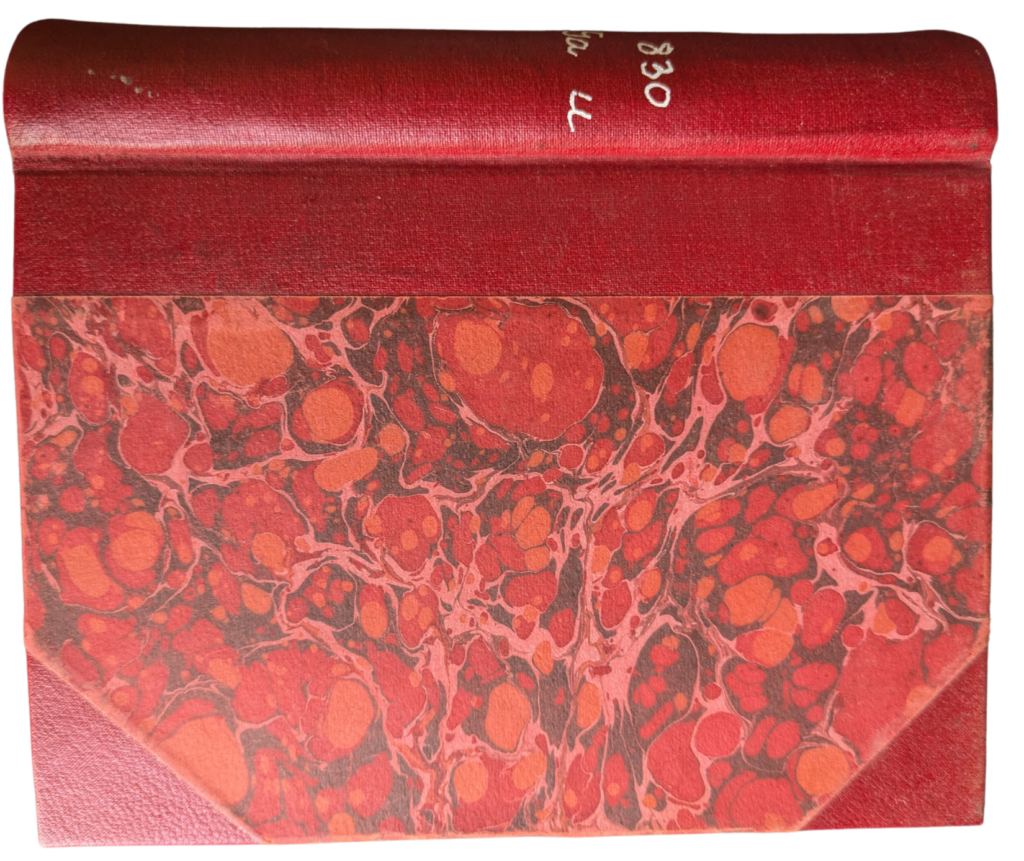

The exhibition “Various Things Happen” was installed in the summer of 2016 and consists of stories and photographs grafted into old, hardbound books that were given to the Museum of Everyday Life after a book clearing at the public library in Ísafjörður. The title of the exhibition alludes to typical stories told around the kitchen table in conversations about everything and nothing. The stories were obtained by participants who showed their family photo albums and shared memories connected to the pictures. Take your time and enjoy the magic of the mundane.

The weather had been crazy for several weeks-we’d been without milk, bread, and meat for at least a fortnight. We always freeze bread, but we don’t freeze milk. We had been without it for some days-I always took milk in my coffee and I wanted milk so badly that I just sprayed breast milk in the coffee. It was a bit sweet, but awfully good.

We stood at the window waiting for the ferry and when it came, we hurried into our coats and rushed down. The women stormed the store-there were nearly fights, people ripped the bread off the shelves. Families with children got priority and there was only one litre of milk per family.

E. B. Suðureyri, 1981

I. When we were moving from Súðavík mom and dad gave us one of those disposable cameras and we were allowed to take pictures of whatever we wanted. Dad took the first picture of us, and then we went out and took pictures of everyone we knew in Súðavík. They were all taken the same day, just one summer day in Súðavík in 1991.

II. Here’s some kid riding around with a bottle on the back of his bike, just to make noise.

III. This girl thought we were playing a trick, she’d never seen a disposable camera. She was sure that it was the kind of camera that sprayed water. She was very skeptical.

IV. My sister wanted me to take a picture of this dog, she went out everyday with that dog. She always put her hand out like this when the dog was supposed to sit still. I wasn’t supposed to take the picture before she was out of the frame, it was supposed to just be the dog. She was really annoyed with me when she saw the picture, but I didn’t have the patience to wait.

V. Of course Bessi, that was the boat in the village. Had to take a picture of it.

VI. We were going to take a picture of my friend but he wasn’t home. So we just took a picture of his grandmother and little sister.

VII. Here the kids would slide down the hill behind the post office, and this is a picture of them.

G. H. H. Súðavík, 1991

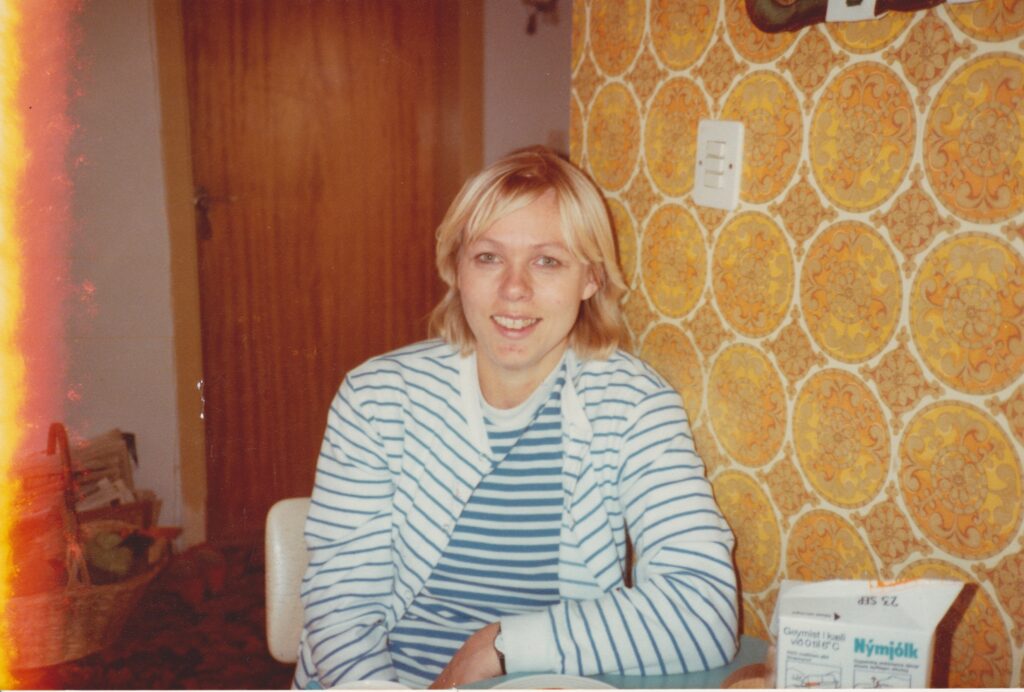

I woke up kicking one night. My leg didn’t stop, I found that very funny at first. Then the jolts started moving up my body and I said to my husband: “This is strange, maybe I should call a doctor.” Then I thought: “No, surely it’ll stop, I’m not going to go call the doctor in the middle of the night.” So it ended up that we called the doctor and he came right away. He realized immediately what was happening. I went straight to a CT scan here in Ísafjörður. They found a tumor that was the size of a lemon, one of those organic lemons. I was sent to Reykjavík by air. The x-ray technicians were on strike, so when I got to Reykjavík I wasn’t able to get an x-ray until the next day, so I waited one day to find out if the tumor was malignant or benign. I liked waiting that day because I was so sure that the news would be something bad.

I was glad to wait one day to have some hope.

It was amazingly good to be rid of that, to just realize that for ten years I had been tired because I had a brain tumor, not because I was lazy. I had just become so terribly tired. We were taking over the farm the day I was diagnosed with the brain tumor. I had to actually hurry to recover so I could go help out in the countryside. The focus was just on the countryside, not on being sick.

I just had to be alright for lambing. That’s just how it was.

M. S. Ö. Ísafjörður, 2013

Do you see the woman? That’s at Óshlíð. When I drove from Bolungarvík to Ísafjörður I always saw a woman on the beach, but no one else seemed to see her. She sits somehow and looks to the side. I didn’t see her when I was driving from Ísafjörður to Bolungarvík, but always when I left Bolungarvík I watched her. My woman.

I was actually thinking about her the other day, missed driving there and seeing her, because I went there for many years but now there is a tunnel. She’s surely still there. It’s just a boulder on the beach. I obviously stopped especially just to take a picture.

I am very glad, because that’s the only picture I have of her. I imagine all sorts of stories about it, she was a woman and I cared for her. I also found it a little nice that no one else saw her, as far as I knew.

H. O. Bolungarvík, 1995

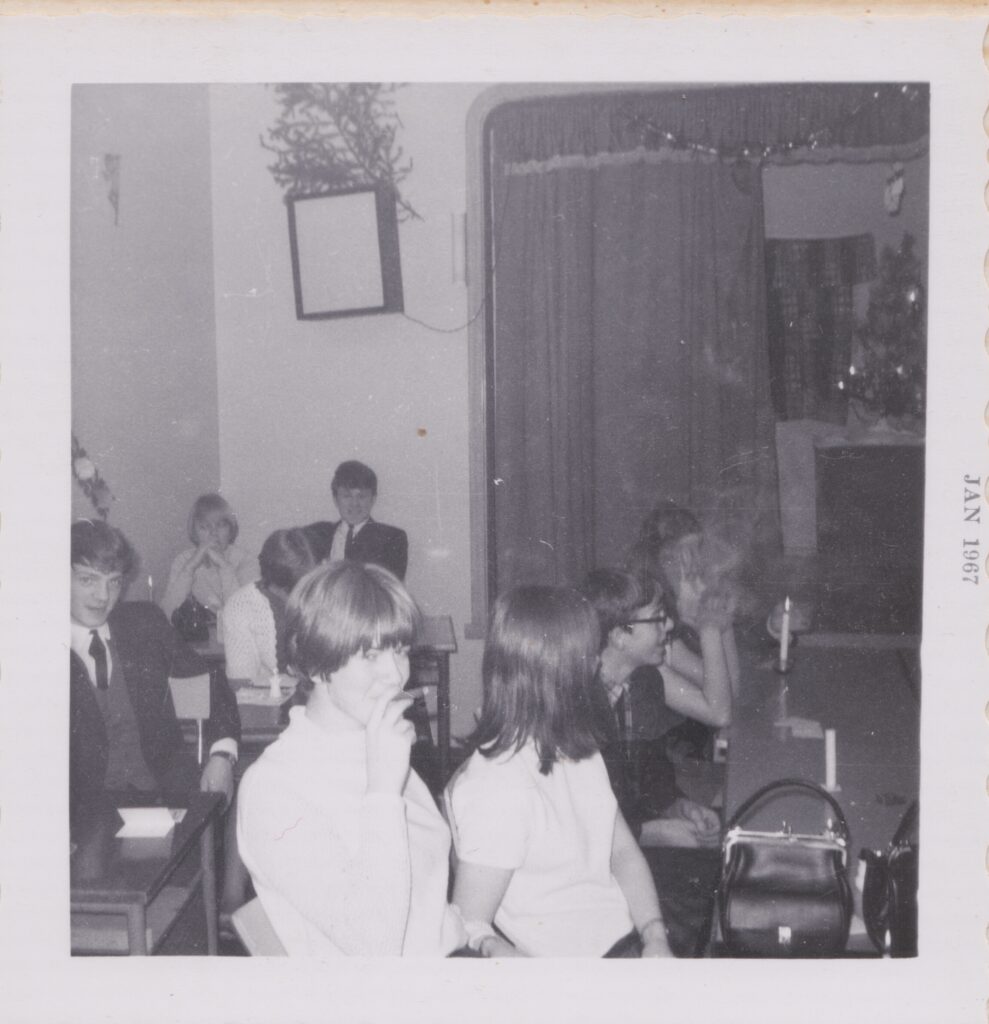

This picture was taken December 1st. At that time, all the main festivities were at school. Those who had long hair went to get their hair done and get an updo. The day after was gym class, and they were all watching from the benches. You had to take care of your hair.

G. S. Ísafjörður, around 1966

The countryside. Lovely. There were always some dogs, and with regular intervals they were named Lappi.

M. H. J. Dýrafjörður

The best day to date it is that it was the second year that the herring were in Hvalfjörður. I was captain of Örnin, an approximately 19 ton boat, working for Örnólfur Valdimarsson. It happened that the co-op had received apples and oranges, but Páll Friðbertsson who ran the store here hadn’t gotten any. We are brothers-in-law and I thought it was too bad not to be able to get him the apples, so I felt driven to help him too.

Two days before Christmas Eve he suggests that I should pop south to pick up the apples on Örnin. I’m up for it, so I go home to my wife and say that I’m going to Reykjavík. She gets really nonplussed. Egill Kristjánsson was my engineer then, and I got Marteinn Friðbertsson and Gíslí Páll as deckhands. They were both 16. We set off between1pm and 2pm. It went fairly well and we arrived to Reykjavík at 1pm on the 23rd. Örnólfur lived on Langholtsvegur and so I went to his house. He insisted that I take apples and oranges for the co-op in Flateyri as well, and that was it. The train was totally full.

I’m at his place around three o’clock when the weather report comes on. The forecast is for gales in the southwest on Faxaflói Bay, with storms likely off of the Westfjords the next day. Ragnhildur, Örnólfur’s wife says to me: “You’re not going out in this weather.” “I have to” I say.“I promised to be back west before Christmas.”

Then I say goodbye. We set off at about 4pm on the 23rd. We raised the jib and the mizzen since the wind was blowing southwest and it was advantageous to have some of the sails up. When we were done with that and are out on the bay, I went to have a little rest. I’d been standing over all of Faxaflói Bay and more than that on the way south, and was going to rest for awhile. I get into a bunk, but then the sea breaks against the port side in such a way that it makes everything creak. The weather was picking up past the Garðskaga peninsula. All the floats went overboard. It all hung together because we had secured everything tightly before we left. I wanted to bring it all in, and we managed it. It ended up that I didn’t get to rest at all-instead I took over the steering and stood there all the way to Súgandafjörður.

Out of Dýrafjörður I go to the front to try to send word over the radio. There, both of the deckhands are in their bunks and our passenger is lying on a bench. We hadn’t had a single bite to eat. It wasn’t possible to use the heat because everything was full of ash and debris. The guys hadn’t even taken an apple out of the box to eat. They hadn’t dared to, as it was considered theft. A large part of the radio gadgetry had come unscrewed and fallen under the caboose, so it wasn’t possible to make a call. We couldn’t listen either. Páll had sent out an announcement on the radio-he was scared to death and regretted having sent us south. He felt like he was responsible for our lives amidst all this damned silliness.

We continued on around the Barði. The flurries subsided every now and then so that the promontories could be seen, but otherwise we just had to trust the compass.

Now came the worst, and it was going into Önundarfjörður. It was an absolute hurricane and we were always coming across lights. We were always turning away from other ships-there were trawlers floating all around Önundarfjörður. The lights came one after another, all of a sudden out of the darkness.

We made it to Flateyri all the same. Hinrik Guðmundsson was there in a car to pick up the apples. He said there had been an announcement on the radio that there was a boat on the way from Reykjavík to the Westfjords, and ships were asked to give assistance and information if they became aware of anything. He says to me: “You’re not going any further. Go up to Sólbakkabryggja pier and moor there.” I tell him I’ve promised to bring the apples. It was Christmas Eve between seven and eight o’clock. We continued our journey immediately.

I launched the lugger right away at the tip of Flateyri and set course out of the fjord. There’s such a blizzard and raging wind that I have to sail out beyond Sauðanes, navigating according to the wind and the clock, but it helps us that the tide is coming from the south, since if it is from the north, the sea can be extreme off of the peninsula. So I turned and set course for Galtartanga and when the gusts began to soften I knew that we were under Galtartanga, and I headed into the fjord.

Egill moors the lugger and I kill all the lights in order to see better from the boat. The first thing I saw when we came in was Draupnirat the moorings. Then I turned on the lights. Jón Valdimarsson, who was there on behalf of Páll Friðbertsson, sees this. He immediately goes to Ísversbryggja pier where we are docking. It is almost eleven o’clock on Christmas Eve. The first box of apples that came on land was sent to my house.

G. G. Suðureyri, 1948

Published in Ísfirðingi, volume 21, 1971

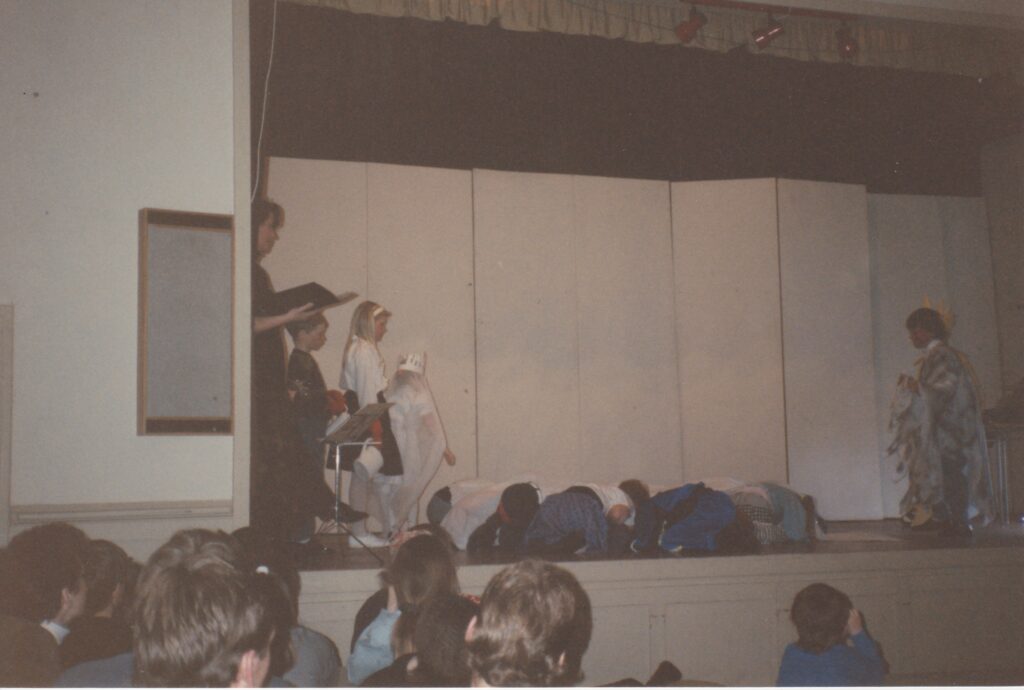

It was the annual celebration at school. Everyone was a flower, except for me. I was the snow. I was a little frustrated because the flowers got to be on stage much longer. The snow just came to take the flowers away. This other kid was winter and I was the snow, we came together. When the sun had been shining, then the winter and snow came, and we spread a blanket over all the flowers. This is when we’re doing that.

G. H. H. Súðavík, around 1991

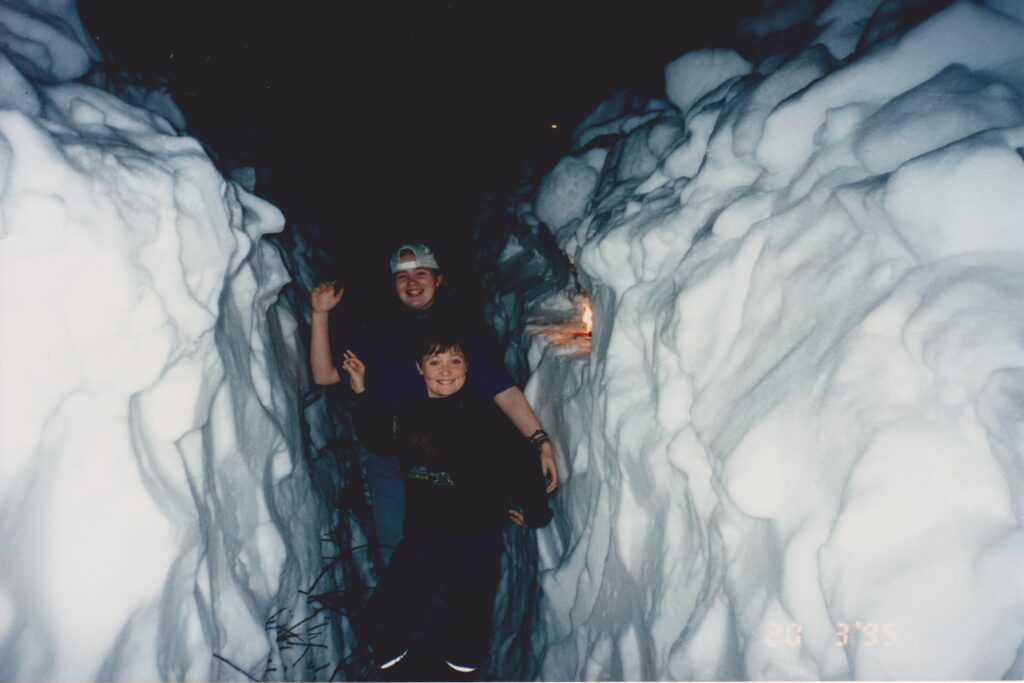

So much snow, it wasn’t fun to jump down off the roof anymore, it was only 5 cm down.

G. H. H. Bolungarvík, around 1995

I am fortunate enough to have had many wonderful times at Hesteyri, Jökulfjörður. As many people know, an old uninhabited village is located there, which was abandoned in 1952 – the old houses that remain are being used as retreats by the former inhabitants’ descendants, which is a new thing, particularly in summer. I have visited Hesteyri nearly every year since I was born and savored time there with my grandparents, parents and other family members.

The older I get, the more frequently I visit this special place on my own – often entirely alone – no one else around save for the birds and foxes and perhaps the odd mouse. In our house we have a loft to sleep in and a trapdoor in the floor. During those stays on my own in the house, I have experienced more than once or twice, someone walking up the stairs – lifting the trapdoor and having a peak. Only to have it shut back and I’ll hear footsteps on the way down again.

I will admit this has scared me a bit, although the feeling is not terrifying, more like someone watching over me. I like to think that my great grandparents are checking in to make sure I blew out the candle and the like. When I experience something like this I have always found it helpful to recite a preface from the folk tales of Jón Árnason, used to invite elves to one’s house on New Year’s Eve: “Come those who wish, stay those who wish, go those who wish, harmless to me and mine.”

A. F. E. Hesteyri, 2016

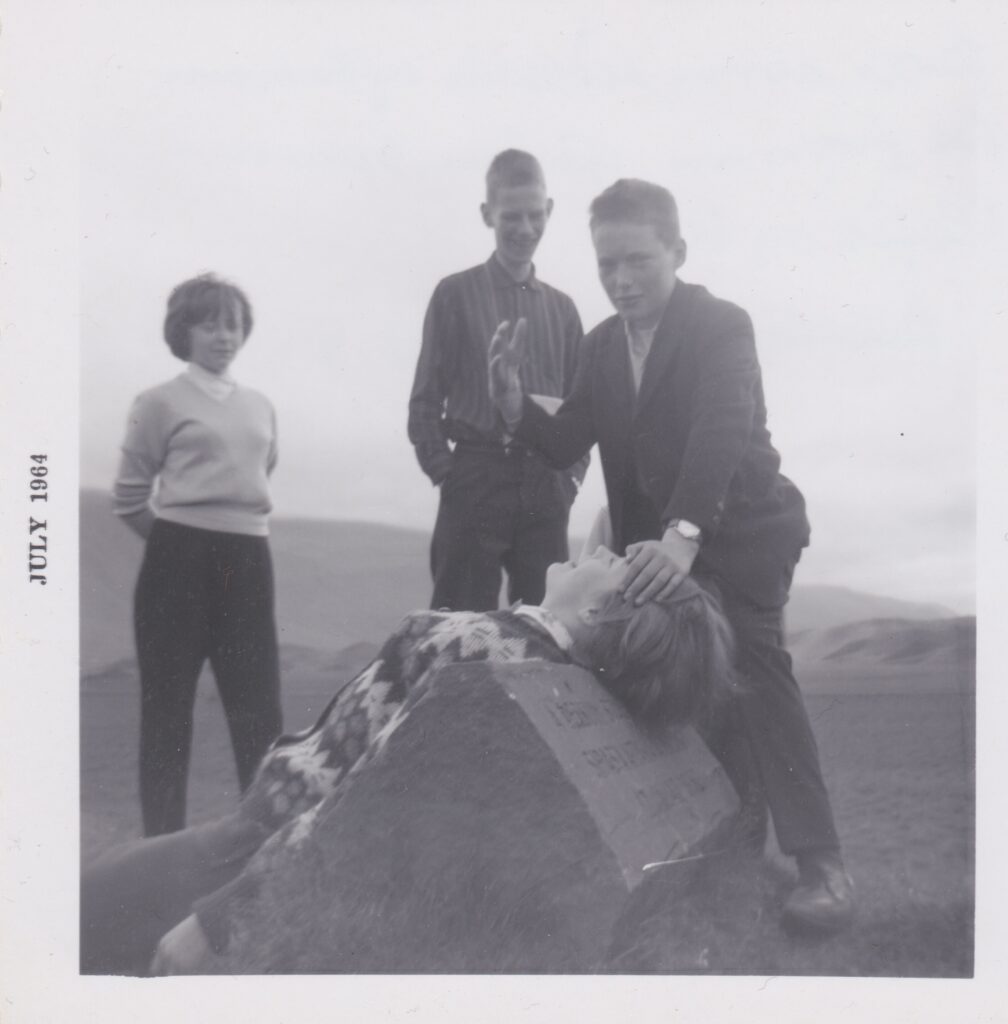

This is on a school trip. Here we are at the memorial at Þrístapi where Agnes and Friðrik were put to death in the year 1830. It was the last execution in Iceland. There are Gerður, Svenni, Ólafia and Óli. Here he is cutting her head off. They are now married.

M. G. Þingeyri, 1964

Here are the tunnels now. It was so wonderful when they opened, it was the most festive day that I have experienced here in Bolungarvík. It was absolutely wonderful. The town treated everyone to food, and there were all kinds of entertainment. But the road around Óshlíðhad been beautiful.

H. S. Ó. Bolungarvík, Óshlíðargöngin opened for traffic the year 2010

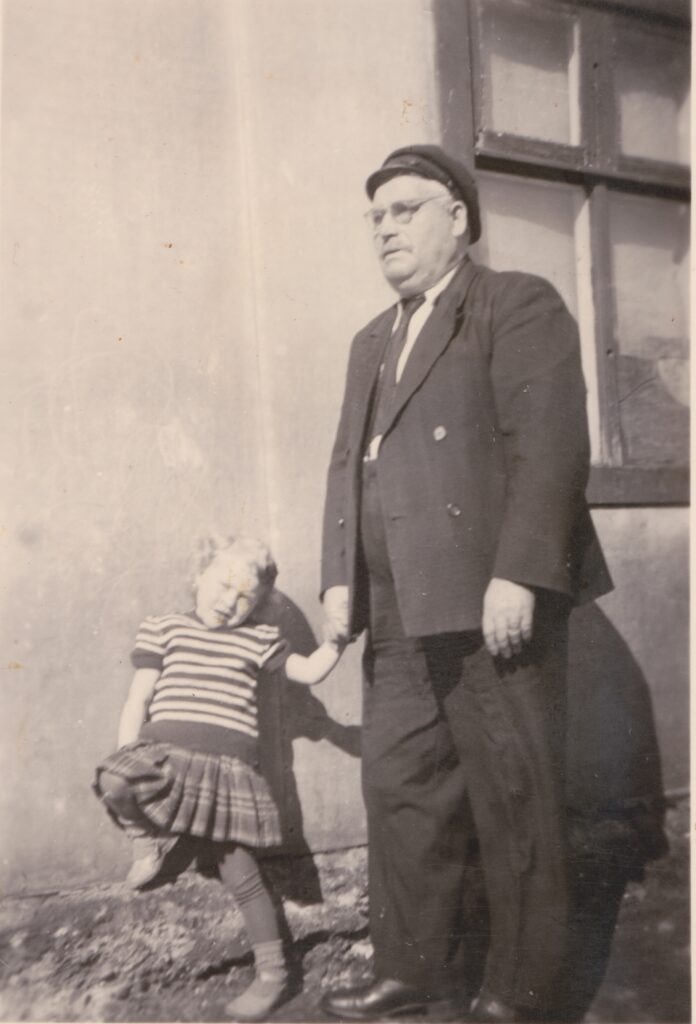

My mother had written her grandfather a letter, saying she was going to give me up for adoption. They had decided on it, they were going to give me to grandmother’s sister who only had one boy. She wasn’t able to have children herself, and had taken in one boy and was ready to have me too.

So my mom took me, the day before Sailor’s Day, to give me up. She stopped in at her mother and grandfather’s place-they lived together-and asked whether the little girl could stay over for one night. The grandfather fell in love with the child, and the next morning when my mom intended to give me up, he said:

“You’re not taking this child.”

Yes, she certainly was.

“No. For one thing, you’re not old enough to give up the child, you’re only 16 years old and you have to have permission from your mother to give up the baby and permission from me as a foster-father. You’re not taking this child from us. If you’re going to give it up for adoption and are absolutely determined to do so, then you just leave it with us. Nothing but death will separate me from this child” He said.

I didn’t know anything about this until grandmother told me about 20years ago. I’d found a letter that great-grandfather wrote in about 1950and in this letter was a poem he had penned in old Norwegian, called Homesickness. He was from Norway and in the poem he described enormous homesickness.

I asked grandmother: “Why didn’t he go back to Norway? He wasn’t committed to anyone, not to you?” “Yes,” she answers, “he was committed, because he promised when you came here and your mother was going to give you up, that nothing would separate the two of you except death. He was waiting for you to grow up so we could all three go to Norway. He didn’t want to go without you.”

I was 12 when he died.

Naturally I burst into tears when I read and heard that because I found it so sad. I felt that I owed him so much.

I went to Tromsö, Norway, for a conference, and I took the letter with me. I went to the top of Storsteinen mountain over the city and read the poem out, loud and clear. I had delivered those words in Norwegian. I felt like somehow I had to do something, it was such a great sacrifice, to sacrifice himself like that for me as a child.

K. S. Ísafjörður, 1947-1993

When I was in my first year of high school, my grandmother sent me money in an envelope. On a slip of paper in the envelope was written: “If you buy yourself booze with this, then I hope you get diarrhea. ”That was the only letter she ever wrote me.

M. H. J. Reykjavík, around 1984

My parents were crazy people, of course, they saw an advertisement in the paper about an available position as the light house operator at Galtarviti, and they just said hey! Let’s apply for that. They got the job and moved, 22 years old, with their one and two year old daughters to the remotest region in Iceland. It wasn’t possible to get there by land, but the coastguard came with supplies once a month. Sometimes people came during the winter on snowmobiles.

There were no phones, only a radio that they used to report the weather, which they did every three hours, 24 hours a day. We went on holiday twice during the two years that we lived there, and both times we sisters got sick. We were just in isolation there. I was accident-prone and a few times we needed a doctor to come and give me stitches and such. My parents didn’t understand why grandma and grandpa were so unhappy with it. I learned to make calls on the radio and once I snuck up and used it to make a call to Ísafjörður: “Ísafjörður, Galtarviti, Ísafjörður, Galtarviti.” Then I was connected to the telephone operator in Ísafjörður, and from there was connected to mom’s sister in Kópavogur, in the south of Iceland. When mom and dad came home, I was sitting at the radio talking to her.

I’ve only been twice to Galtarviti since then. I went there on a snowmobile with dad when I was 12. Some jar up on a shelf caught my eye-I remembered it from when I was little, and it had been in the same place the whole time. I remembered of course bits and pieces of having been there, and then I came back and it was like: “Wow, everything’s so small,” because in my memories, everything was so big.

G. H. H. Galtarviti, 1984-1986

Here’s me during lambing. I actually thought it was appropriate to help all of the ewes give birth, whether they were struggling or not. Here’s grandpa letting me help. You just pull and put your hand in. I thought it was awesome to have to go in and loosen things if they were tangled, feel the feet and pull them out.

H. O. Ingjaldssandur, around 1984

There’s just blood being stirred in this bucket, and then in the other bucket the suet has been added. Here my mom is sewing the membrane and that’s Sirrý, she’s probably filling the bags and putting them inboxes for the freezer.

M. G. Þingeyri, around 1986

Potato boxes. They remind me of a horror story from my childhood in the potato garden.

It was always putting down potatoes and pulling up potatoes. I have two older sisters, we are five siblings altogether and I’m the middle child. My sisters weren’t really that mean to me, just in the way that it’s normal to beat up one’s younger siblings. The pecking order. Except sometimes they liked to mess with me. Once we were pulling up potatoes and my hand touched the so-called mother potato, big, slimy, disgusting. I didn’t actually know what it was, so they told me that that was the mother potato and she became like that because her children sucked all the nutrients out of her. I had a fertile imagination and I transferred that to our mother and was terrified to think that our mother would become like that after we were finished sucking everything out of her. Slimy and disgusting, dead somewhere, because we had sucked everything out of her. Because her only purpose was to nourish us.

It was just all of those feelings together in my little child’s heart, especially the fear and shame over the fact that we were going to treat our mom that way.

M. H. J. Dýrafjörður, around 1970

There was a great dance and band culture here. When it was more isolated here, there was a lot of social life. There were maybe dances at two different places at once, and the main goal was to get the girls from the School of Home Economics to your dance, because then the boys would follow. There were messengers sent with tickets out to the shops, and whoever got the girls won the prize, and that’s where the dance would be. The other was called off.

S. E. Ísafjörður, around 1965

We went to the store when the weather let up after the avalanche in Flateyri, we had all been inside and everyone was in shock.

Then it became brighter and all of a sudden the mountains appeared. People were of course preoccupied with the fact that an avalanche could happen. So I walk out of Sólgata with a sled, on the way to the store. Nothing had been shoveled. People were coming down from the upper part of town.

Everything was white, then I saw a black clump set off to go downtown, to the store. I associated that so strongly with the countryside, the sheep in the snow. When the first comes and then all the rest subsequently follow, that kind of path down each street. Then the group became bigger, denser, and wider. Like walking tussocks. Everyone was so depressed-there was so much sorrow, such gloom. A paralyzed atmosphere. I got to thinking about sheep of course; one connects with the things one knows.

M. H. J. Ísafjörður, 1995

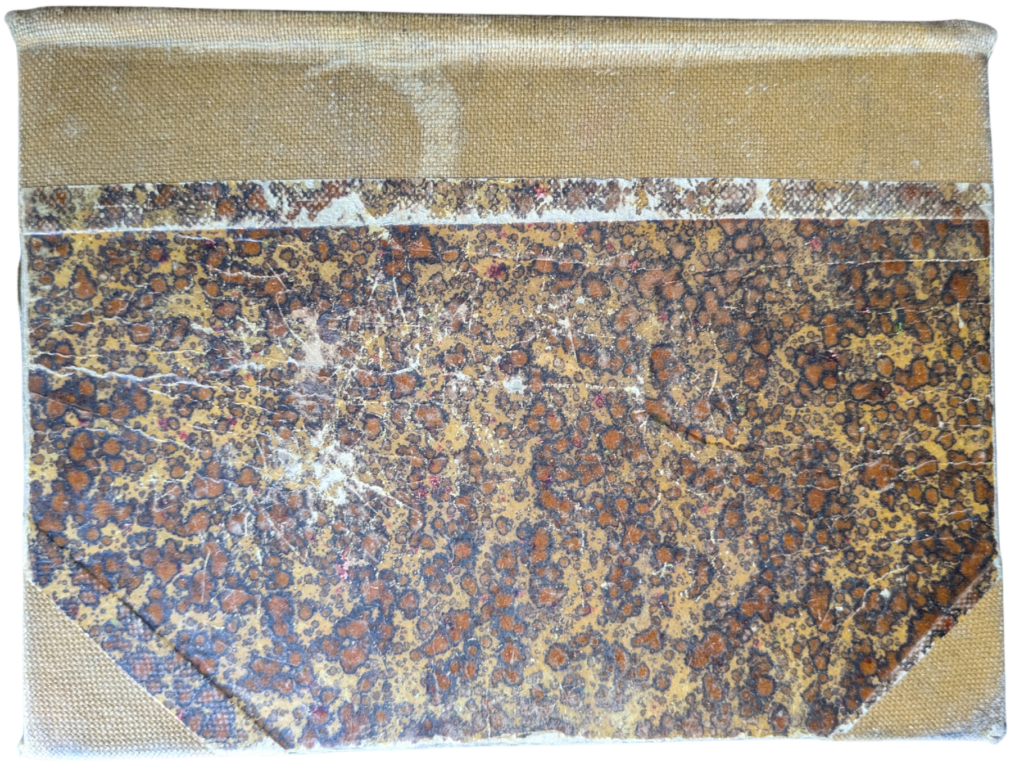

think I was 10 years old when I got my first new notebook. Grandpa used to make all the books for me. He took wrapping paper, ironed it, bound it together, marked and drew the lines himself. I stuck them into a used book that I got from relatives so that the kids didn’t see what kind of notebook I had.

K. S. Ísafjörður, around 1957

There is a certain frequency or sound that I sometimes hear, and when it happens, it’s like someone’s snapped their fingers and I’m in my grandmother’s cellar.

There, cows were milked by hand and milk and cream were being separated. She was of course all into the old methods. You got to turn the separator and you needed to turn it at a certain speed. Then came a kind of hum, and to keep the right pace you needed to maintain the tone.

When I hear a similar sound, then I’m back in that cellar.

It’s always semi-dusk and damp in the cellar, always sun in the windows. There was a table with this separator, and I stood there with the window above me. The sun shone outside and so I’d turn and keep the same tone.

No one saying anything, just standing there and turning.

M. H. J. Dýrafjörður, 2016

There we were making prank calls at the telephone office in Ísafjörður. We had a pile of ten krónur coins with us, and two of us or even three fit into the phone booth if we crammed together. We were always phoning some boys and teasing them, in this picture we were probably calling Magnús Scheving, he was insanely cool in the Pepsi commercial, just before he became famous.

M. S. Ö. og Á. Þ. Ísafjörður, around 1991

I took my national level exams here, and there was a tradition then as it is now, to exchange Christmas gifts. We’re smoking. She has a cigar. Fifteen years old. That’s when you became an adult.

G. S. Ísafjörður, 1966

Here we were building a hut in Aðalvík. Grandma and grandpa were so great, I got these planks as a birthday gift, just one bunch of planks, a pack of nails and two hammers. That was the birthday gift that summer and so we built a hut and all kinds of stuff.

You can see that the planks stick out quite far, but we decided not to saw them off. It was just a little shed, extremely fun.

Then late in the fall, grandpa tore the hut down, took out all the nails, packed up the planks in plastic and took all the nails with him in a bucket to Ísafjörður. Over the winter, grandma straightened out all the nails in the kitchen, and then the next spring everything was ready for us again.

G. H. H. Aðalvík, 1992

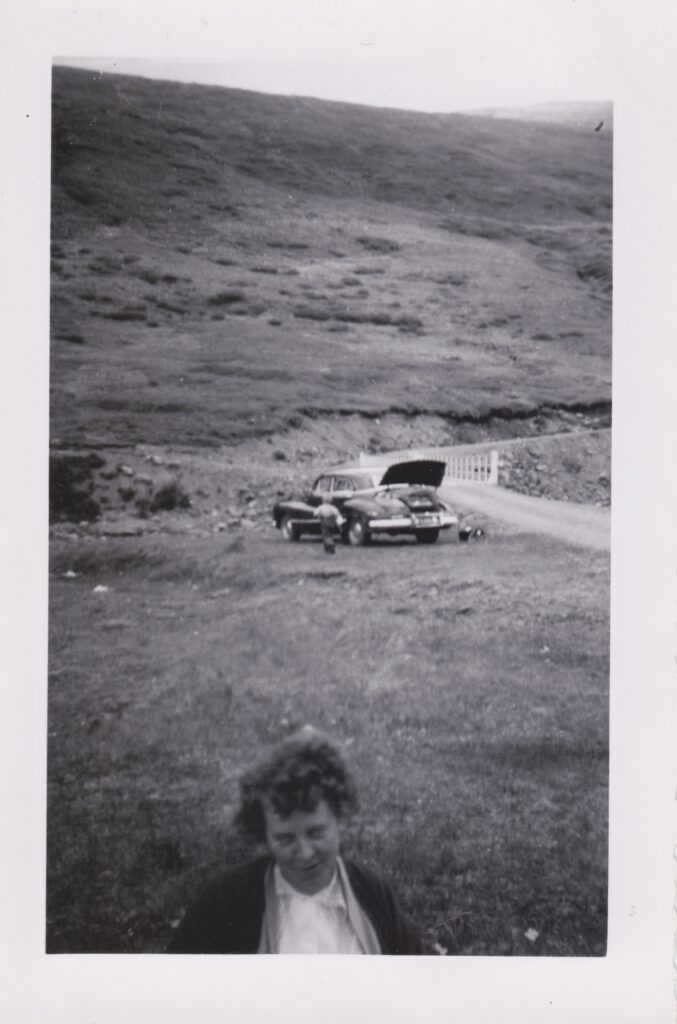

The trip we took to Reykjavík in 1957 was a memorable one. We needed to go from Þingeyri to Ísafjörður and stay there one night. Then we went with our car on the ferry Fagranes over to Arngerðareyri where I believe we camped. Next we needed to stop at Hvanneyri for two or three days because the car broke down. Here we are having lunch in Langadalur, before we went over the Þorskafjarðarheiði mountain road. That’s my mom there in the foreground and Siggi walking to the car. It took us many days to travel a distance that now takes about six hours.

M. G. Þingeyri, 1957

Simson. He was the most remarkable man here by half. He moved here around 1927 and started to plant trees in Tunguskógur, which was Simson’s garden. There wasn’t a single tree when he started out, just some scrub and rocks. He was extremely artistic and handy, and he worked as a photographer and made, for example, the statues outside of the swimming pool. Originally he came to Iceland with a variety theatre from Denmark, they travelled around the country a bit, but when they came here to Ísafjörður, he felt as if he’d always lived here. So he never went back.

S. E. Ísafjörður, story about M. Simson (1886-1974)

Heiða’s bicycle. Springtime hasn’t always come to stay. It sometimes goes away again.

M. H. J. Ísafjörður, around 1994

It is so strong, this clan, this family. This great-grandmother of mine was clearly a very special and powerful woman. She had 13 children and lost her husband when the youngest child was four years old. She had 13 children in twenty years. The oldest child was born 1892, and the youngest in 1912. She gave birth to a boy in March 1903 and everything was fine and all went well, and at Christmas she was pregnant again, very tired and haggard. That’s when her husband wrote to his brother in Djúpið asking whether he could take the baby and foster it over the summer, as she was going to give birth again in mid-summer.

So he took the child, 46 weeks old, and strapped it to himself, in front under his coat. Then he tied a milk bottle at his chest so that the child could drink on the way, and he walked down to the beach near his home and out onto the ice, over the fjord and from there all the way into Ísafjörður with the child in front of him. He walked down to the coast and over the ice all the way to Arngerðareyri. That was the worst. She felt nothing having lost two children, but to see her baby leave like that was awful for her.

K. S. Ísafjarðardjúp, around 1903

This is me and my foster mom. Dad and mom had a few children. They had 15 kids, including six pairs of twins. My mom was sent to Ísafjörður hospital when she had me and my brother because she got so sick. Then all the kids had to be put in foster care, and everyone was willing to help out. I was four days old and was actually just sent across the fjord into Skötufjorður where my relatives lived. When my mom had recovered, most of the children came home again but I remained behind-they didn’t want to return me because I was so much fun.

I was 10 years old when I first met mom, dad, and my twin brother. I thought it was really strange and I was very shy. I didn’t call them mom and dad, but rather auntie and uncle. My twin brother was sent to see me in the countryside so that we could be confirmed together, and that really meant a lot to me. My mom never spoke about difficulties, never. But she told me once that it had been one of the most difficult things she’d ever done to give us up, two days old, and go to the hospital herself. That had been hard. Things happen.

H. S. Ó. Ísafjarðardjúp, born 1926